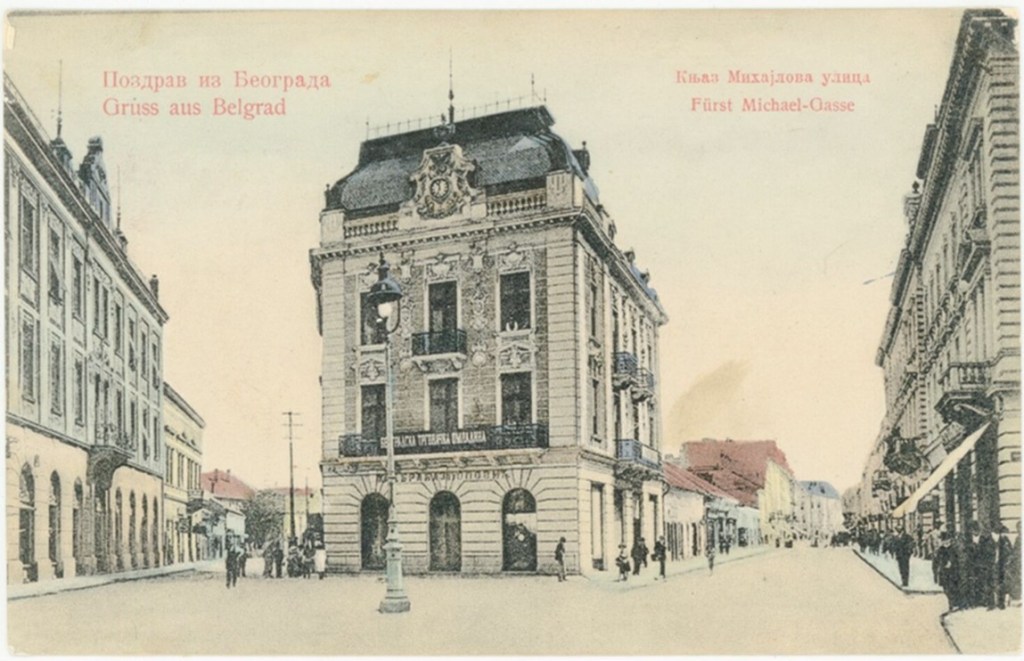

Pre-1954 Library Card for the American Library in Belgrade, Yugoslavia

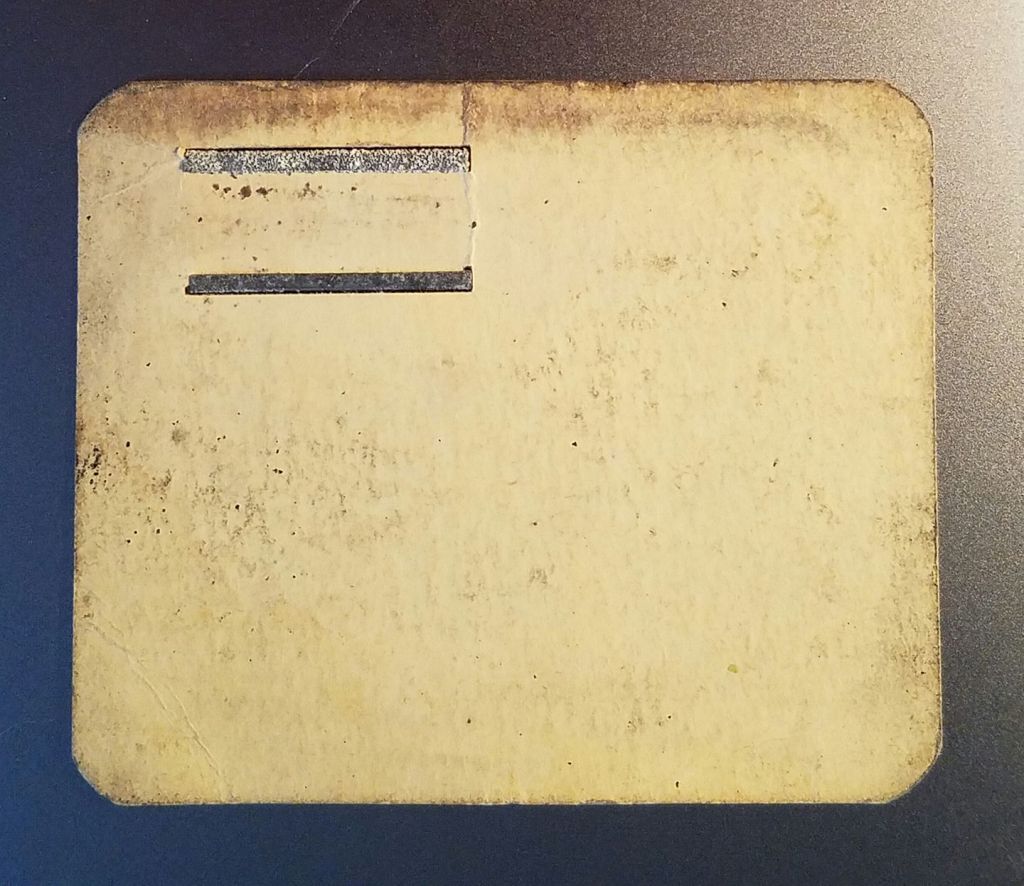

Pre-1954 Library Card for the American Library in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (back)

Pre-1954 Library Card for the American Library in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (back)Department of State’s U.S. Information Service (USIS)

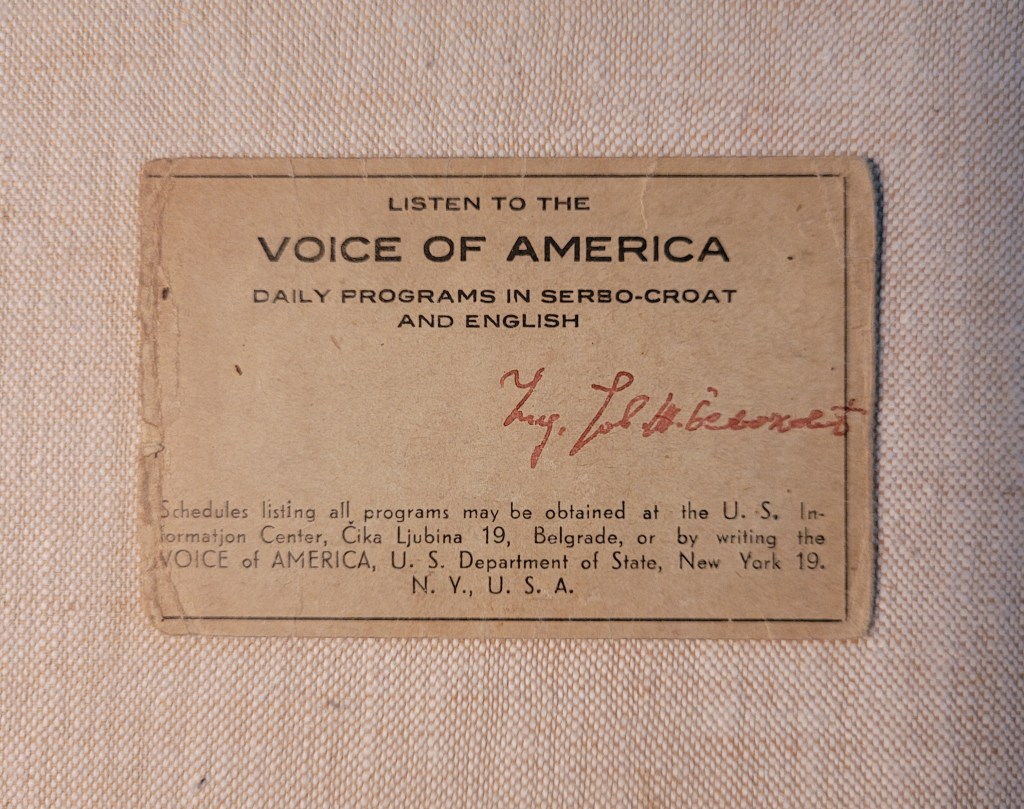

After World War II, and with the passing of the Smith-Mundt Act (of 1948), an act “to promote the better understanding of the United States among the peoples of the world and to strengthen cooperative international relations,” the United States Army in conjunction with the Department of State opened libraries in occupied areas of the world. These libraries, also known as “information centers,” supplied “as representative a collection of significant United States publications in all fields of knowledge.” By 1953, When the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) replaced the USIS, there were 196 information centers and reading rooms, and 34 binational centers for a total of 230 information centers in 75 countries. By 1970, there were 319 centers in 97 counties. In addition to information centers, the USIS/USIA operated state-owned radio broadcasting organizations including Voice of America and Radio Free Europe. (Voice of America and Radio Free Europe are now operated by the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM). The USIA was abolished on October 1, 1999, and information and cultural exchange functions were transferred to the Department of State’s Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs.

The American Library in Belgrade, Yugoslavia

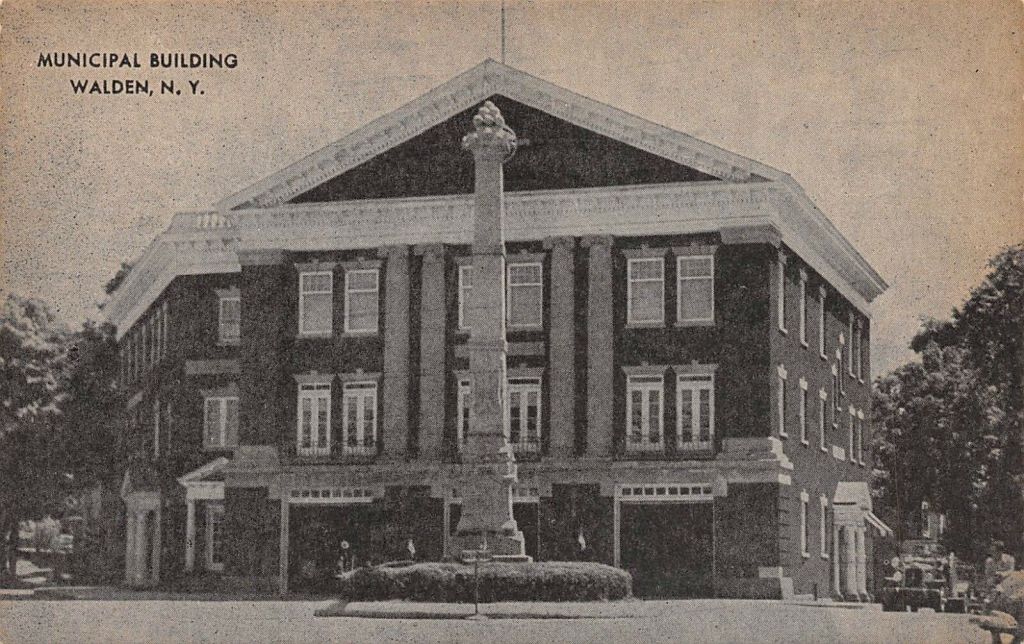

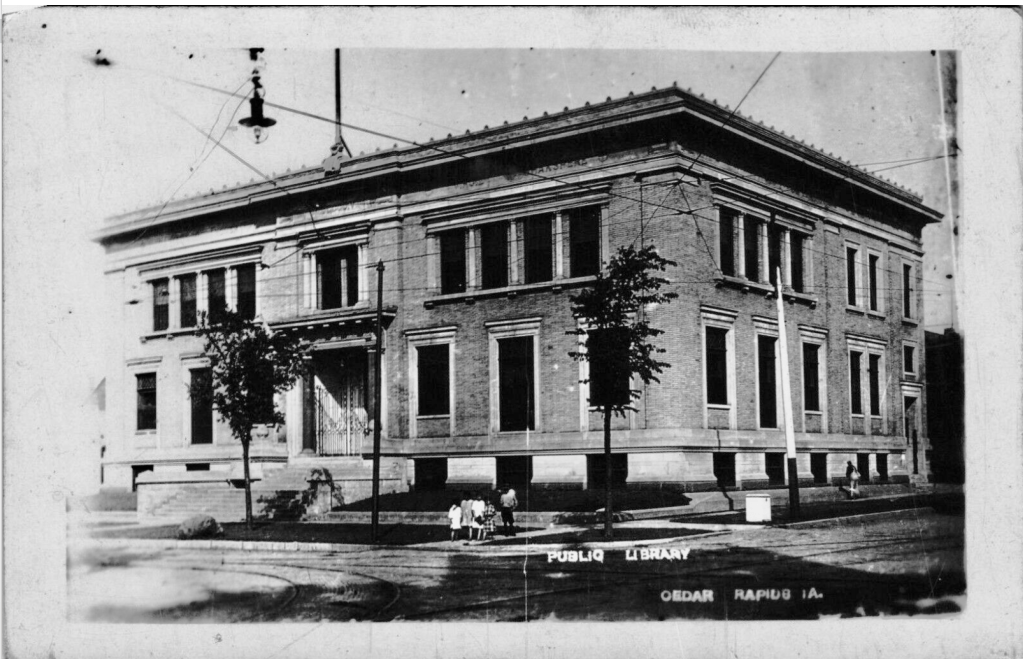

On October 19, 1945, the USIS officially opened the Belgrade Information Center in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Ambassador Richard C. Patterson, Jr. and “a group of high government officials and well-known personalities from the intellectual world” attended the opening ceremonies. Although the USIS typically housed information centers at embassies, USIS officials believed visitors to the Belgrade center would feel intimated entering an embassy, so a “building of a less official nature” at Cika Ljubina 19, the historic Palata Zora building, was chosen as the Belgrade information center location.

Preparing the center’s library for opening day was no easy task. Furnishing the library was a major hurdle since library furnishings were not available in Belgrade. Accordingly, all furnishings had to be manufactured prior to opening the library. This included library tables, chairs, bookcases, display racks and even curtains. Obtaining permits from the local officials further delayed the opening. The cost to open the library was $2,000 USD (approx. $35,000 today).

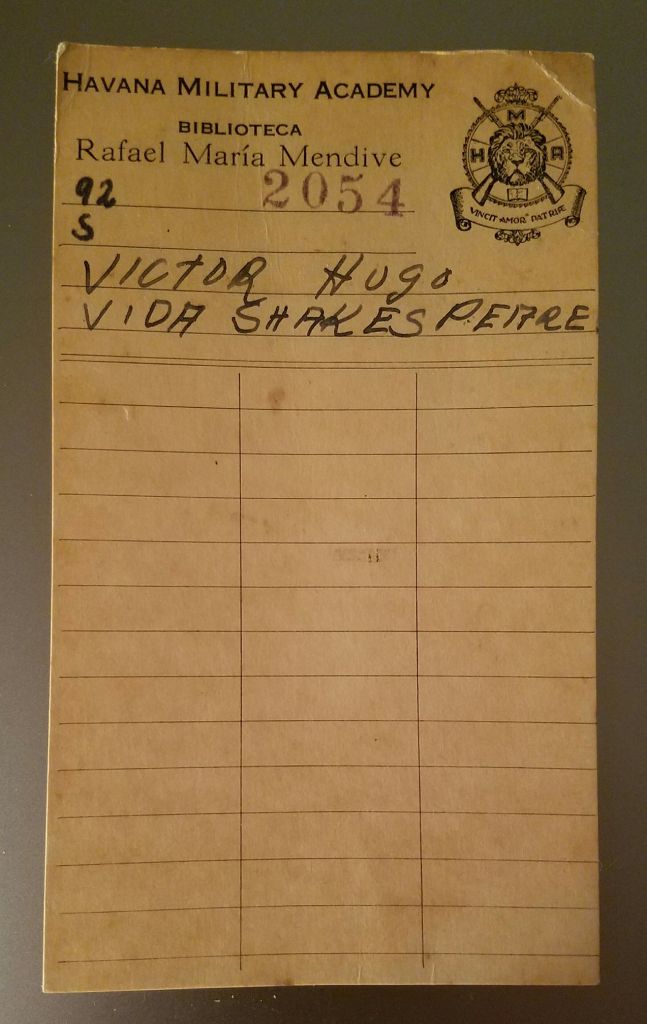

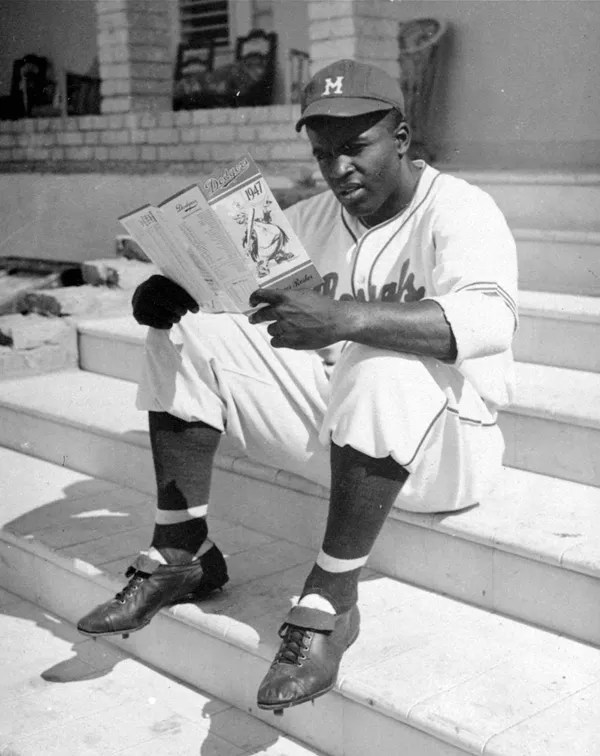

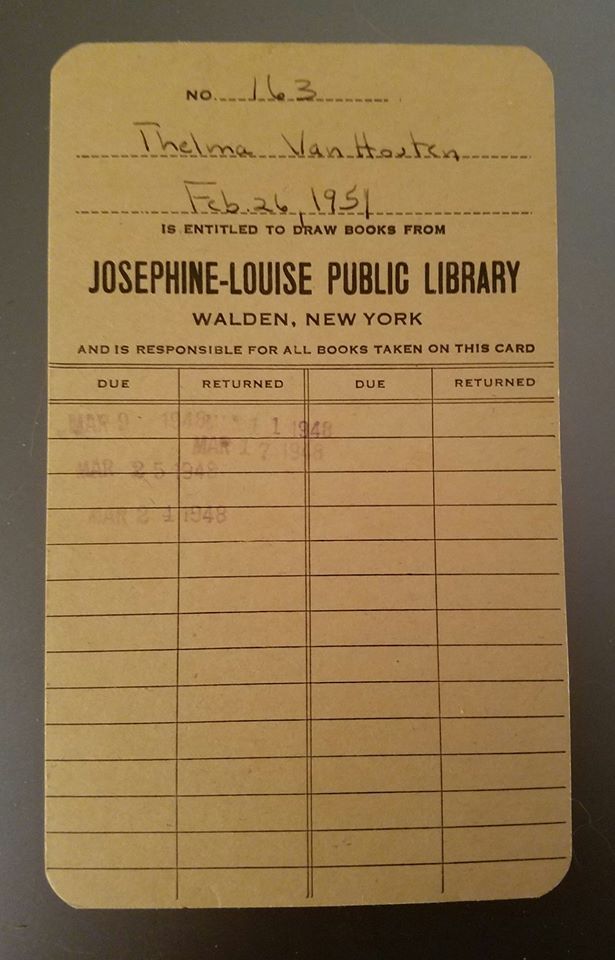

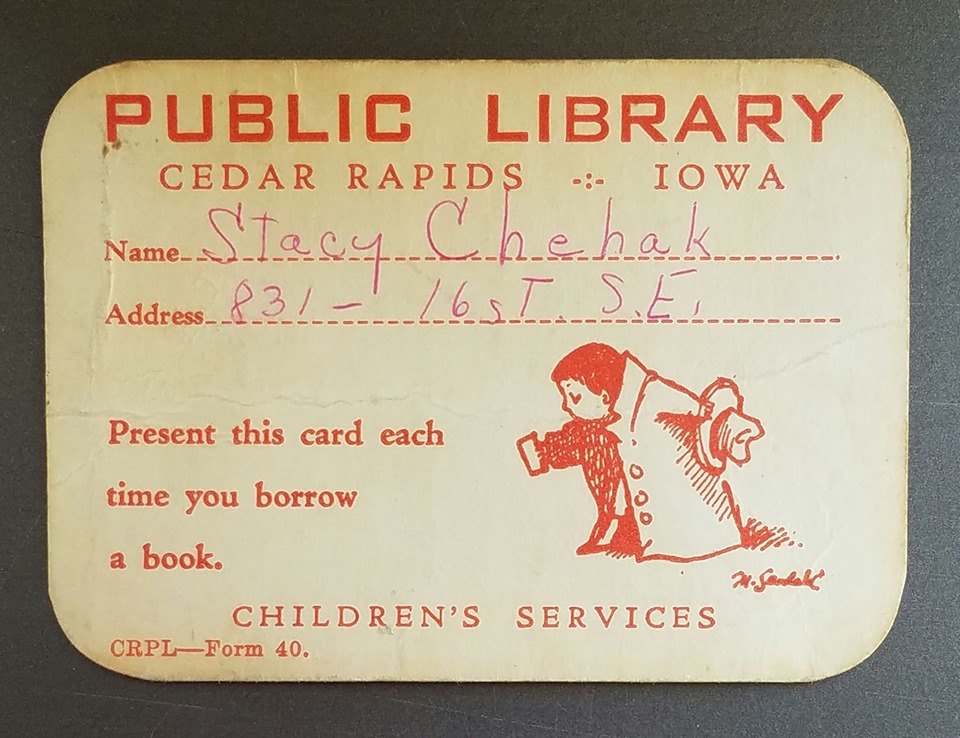

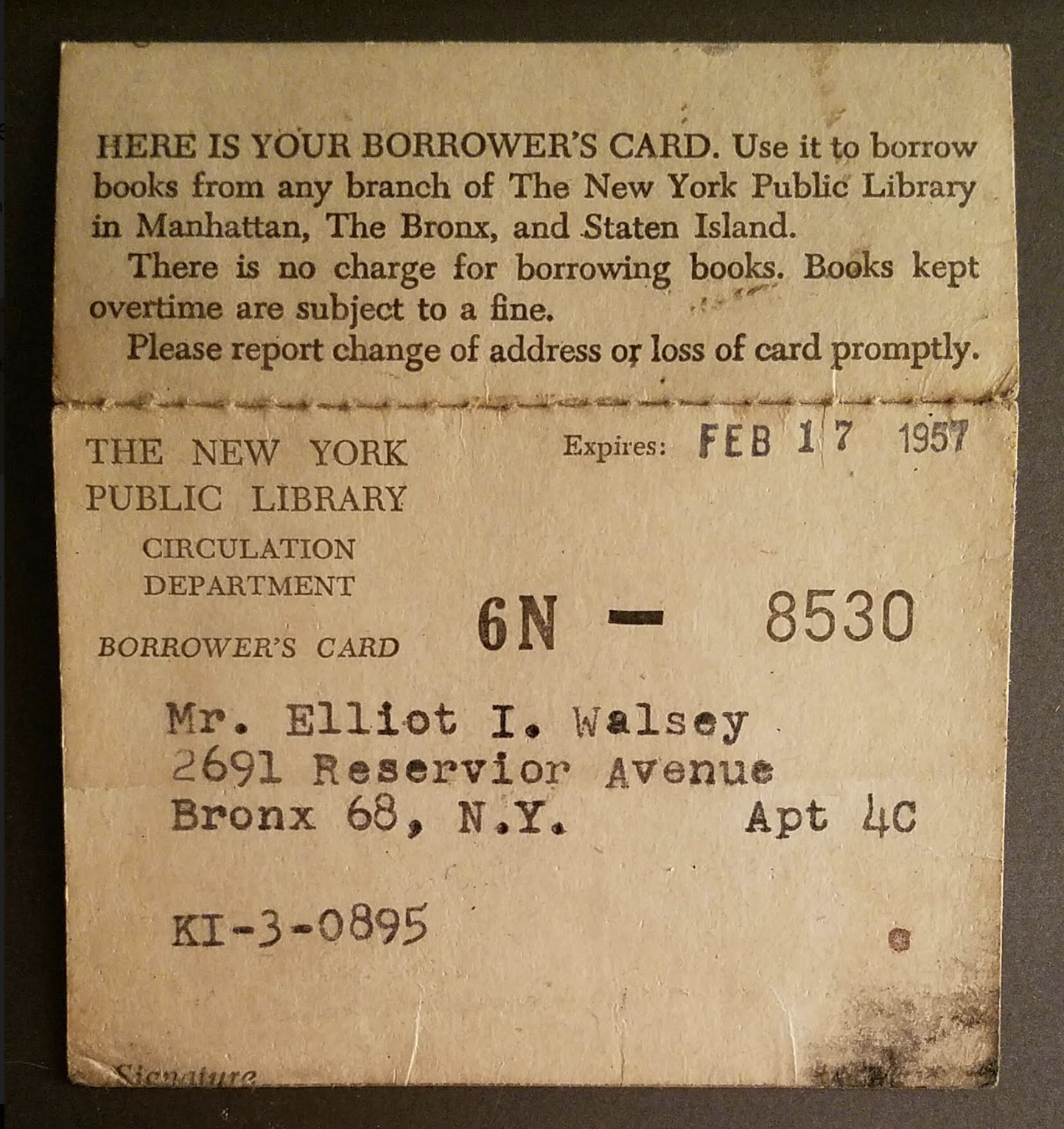

The library was open to the general public from 10:00am-1:00pm and 4:00pm-8:00pm and closed only on Thursday. These hours were most convenient for Yugoslav locals, as most government offices were open from 8:00am-2:00pm. The library reading room contained magazines, newspapers, miscellaneous publications, and a small collection of fiction. A reference library containing scientific and technical publications and books was kept separate. Membership cards were issued to those interested in full use of the center. The management of the library believed that the effort to apply for a membership card limited the casual reader and left more room at tables for more serious students and researchers. For those that held a membership card, fiction could be checked out for one week; however, reference materials were not allowed out of the premises. The library was under the care of a US government “Information Specialist” and three English-speaking Serbians, one of which acted as the librarian.

In addition to library services, the information center maintained display windows on the ground floor in which the currently available books and reading themes were advertised, and an exhibit room with monthly photographic presentations on various subjects related to American culture. The center also presented English-language lectures on American culture, such as music and authors. American music recordings were also available for listening and proved to be in great demand.

According to The Record (Vol. II, No. 5, May 1946), a publication by the Scientific and Cultural Cooperation Division of the Department of State, the library had 2,372 visitors in February 1946. The most popular subjects were American architectures, aeronautics, history, electricity and radio. Reading material on art, chemical research, mechanics, machinery, physics, medicine, music, transportation and American youth were frequently requested.

The American Library Closed

In September of 1946, the information center was closed by the Tito administration after it was accused of “engaging in anti-Yugoslav activities.” Previously, in December 1945, the US government had announced that they would “recognize” the new Tito-led communist regime in Yugoslavia; however “our ambassador was instructed to make it clear to the government of Yugoslavia and the people of that country that our willingness to establish diplomatic relations with the new regime should not be interpreted as implying approval of the policies of the regime, its methods of assuming control, or its failure to implement the guarantees of personal freedoms promised its people.” When this information was supplied to the Yugoslav people, the Tito administration failed to disclose the criticism that accompanied the recognition. Upon learning of this transgression by the Tito administration, the USIS transmitted radio broadcasts of the full US statement and posted transcripts of the statement in their display windows. Locals swarmed the center display windows to read the news causing the local police to disperse the crowds. After some diplomatic negotiations, the center was allowed to reopen three months later on the condition that radio news bulletins would no longer be posted.

The American Library in the News

The Palata Zora

The Palata Zora (English: Dawn Palace) was built in 1904 for royal court jewelers, Constanine and Nikola Z. Popović. The building was confiscated and nationalized in 1944 upon the rise of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). Since 2004, the Palata Zora has been home to the Instituto Cervantes, a worldwide nonprofit organization created by the Spanish government to promote the Spanish language and the culture of Spanish-speaking countries.