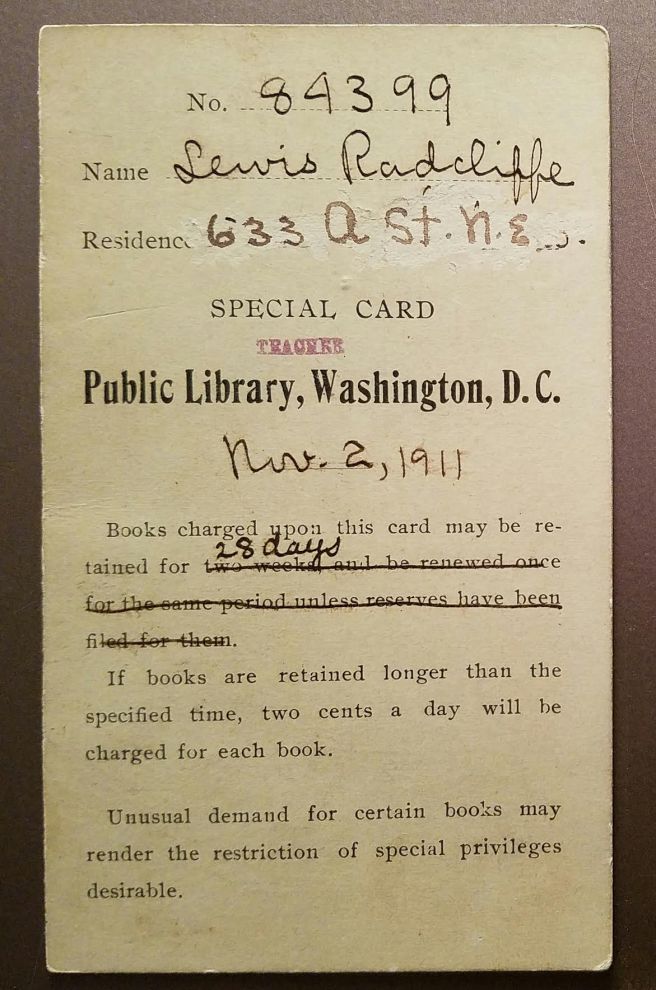

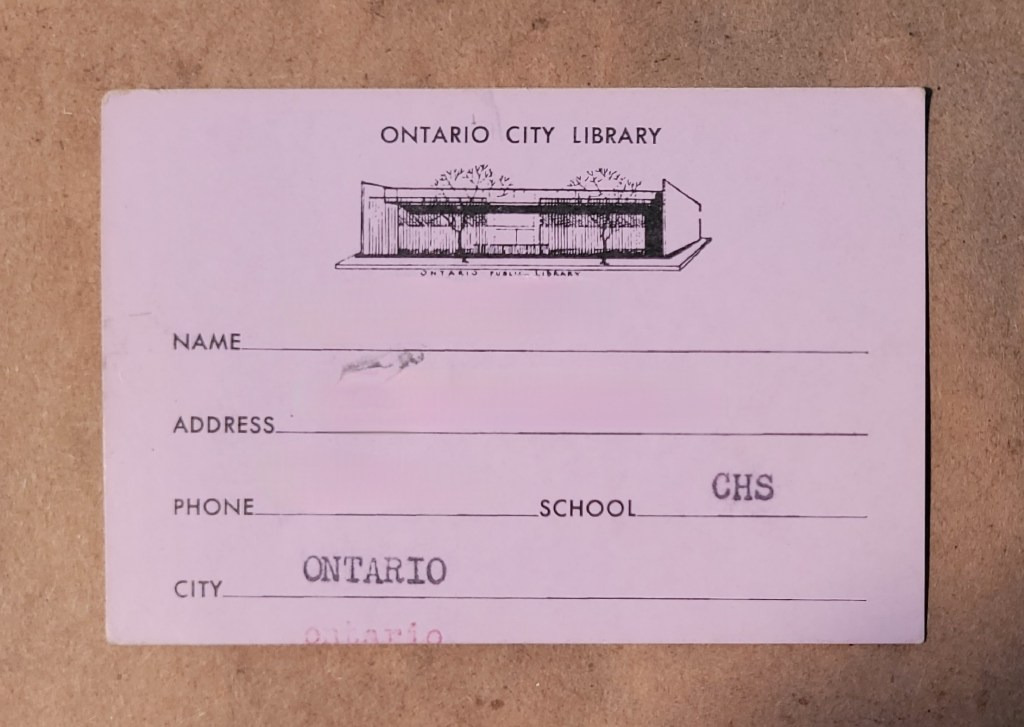

1961-1964 Ontario City Library Card for Chaffey High School Students

(living person information redacted)

Ontario, California – The Chaffey Brothers’ Vision

Pre-1923 public domain publication. No known copyright restrictions.

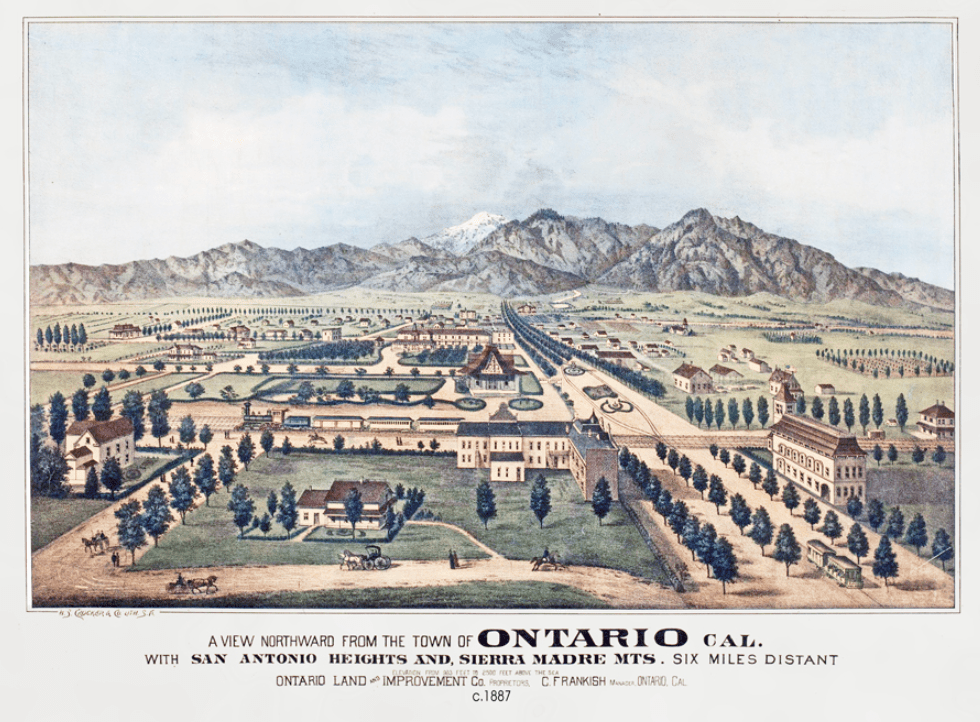

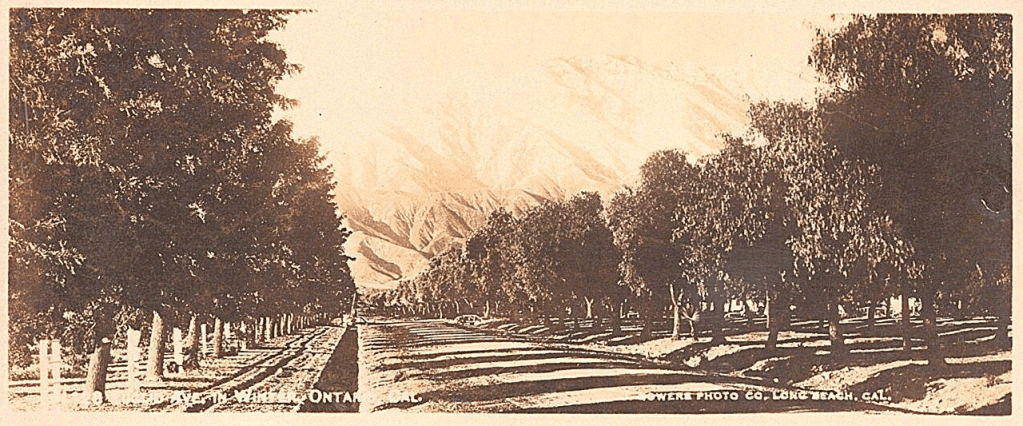

In 1881, brothers William B. (1856-1926) and George Chaffey, Jr. (1848-1938), both engineers from Brockville, Ontario, Canada, began purchasing parcels of land in Southern California with the intention of creating “irrigation colonies” complete with water resources, water-powered cable cars, grand avenues illuminated with electric lights, and convenient access to the existing Southern Pacific Railway. Those land purchases became the Etiwanda, Upland, and Ontario Settlements. Due to the mild winter climate and easy access to water from the nearby mountains, citrus farmers were some of the first landowners in Ontario.

Pomona Times-Courier, 23 Dec 1882, Sat ·Page 3

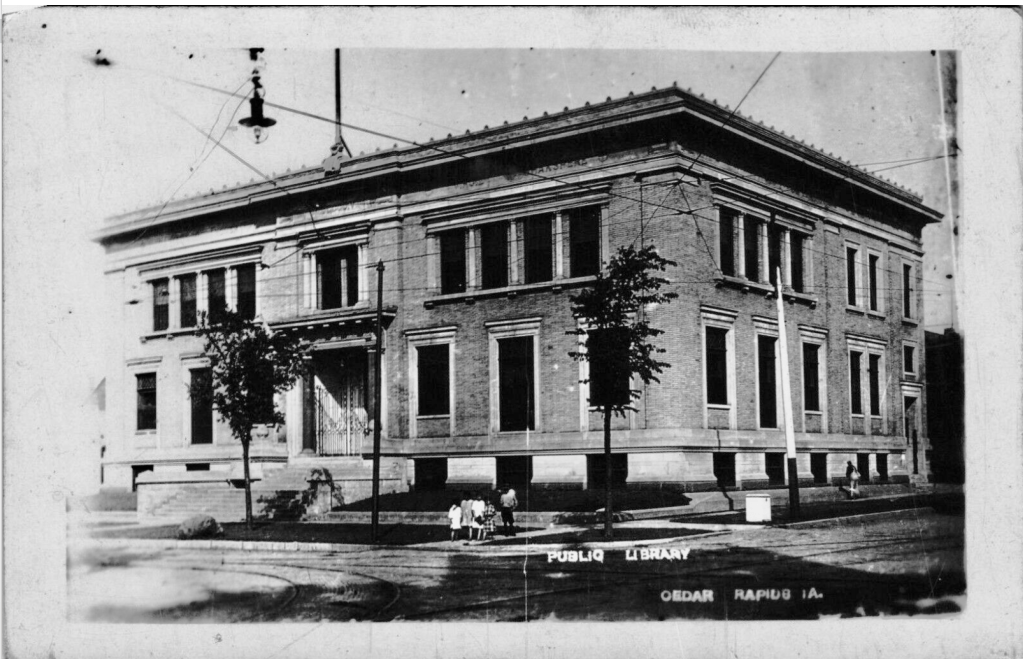

Ontario City Library

The Ontario City Library was established in 1885, according to Publication No. 3, “The Libraries of California in 1899”, which was published by the Library Association of California in April 1900. Although it was organized by the town of Ontario, the library earned its revenue through annual subscriptions of $1.00 and community fund-raising events, such as citrus fairs and concerts. Not until 1902 would the library become a free public library.

One of the earliest newspaper mentions of the “Ontario Public Library” was in 1886 when Richard Gird, a successful silver miner and local real estate investor from Tombstone, Arizona, donated fifty volumes to the “Ontario Public Library.”

In 1894, for the first time, the Trustees of the California State Library recognized and included the “Ontario Public Library” in the fiscal report for the Forty-Fourth and Forty-Fifth Fiscal Years (July 1, 1892 to June 30, 1894). It was noted that the library was “too recently organized to furnish statistics.”

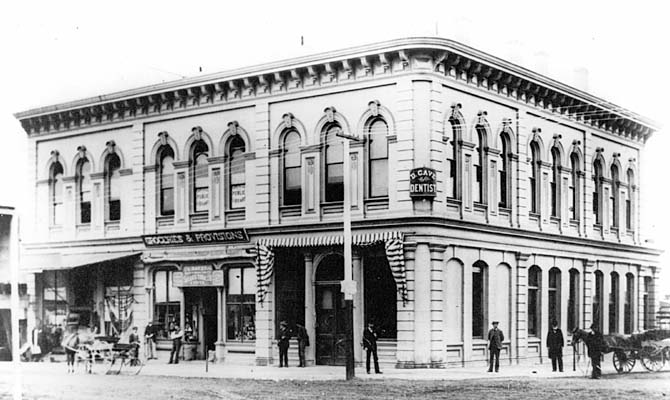

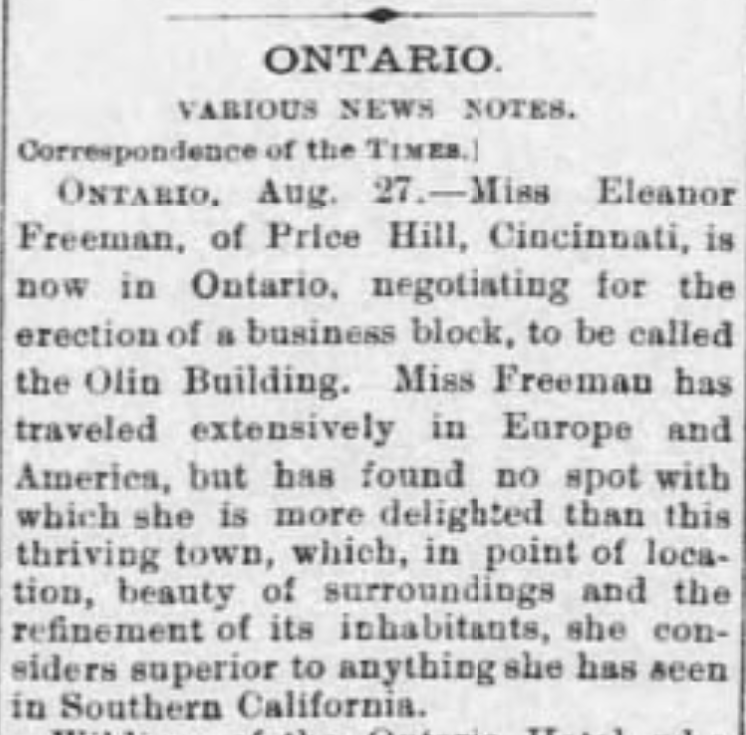

One of the earliest locations of the library was at the southwest corner of A Street (now Holt’s Boulevard) and Euclid Avenue in a 2-story brick building known as the Ohio Block. The Ohio Block was built by Miss Eleanor Freeman (1848-1904) in 1888. Freeman, originally from Cincinnati, Ohio, was so charmed by the weather in Ontario that a temporary three-week stay resulted in the purchase of a twenty-acre tract of land. Freeman and her niece, Mary Ellen Agnew (1851-1914), served as the first librarians.

Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

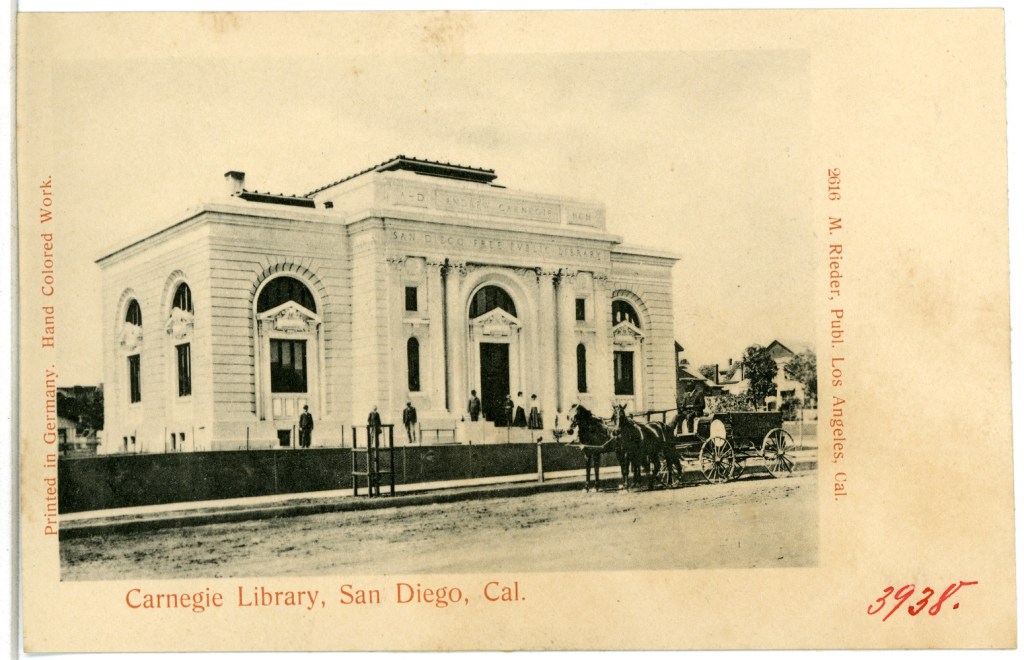

Pre-1923 public domain postcard. No known copyright restrictions.

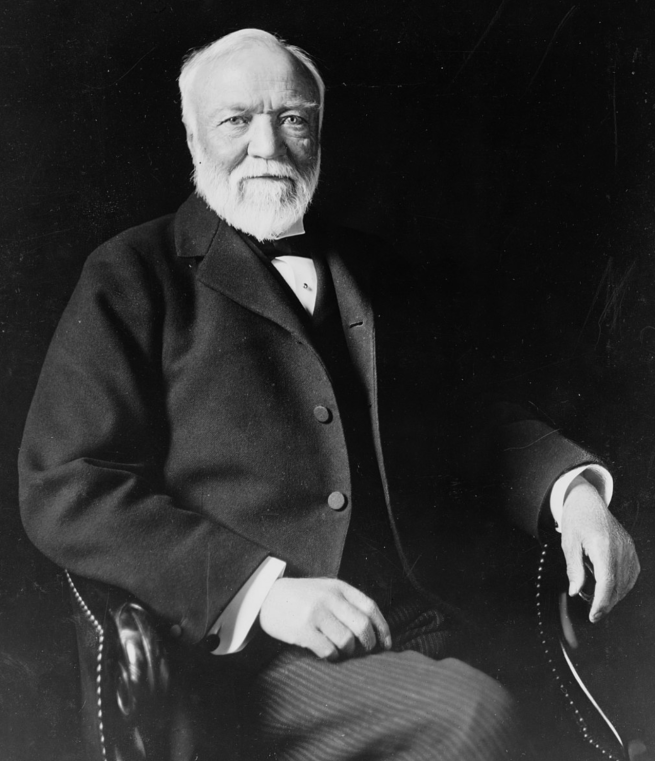

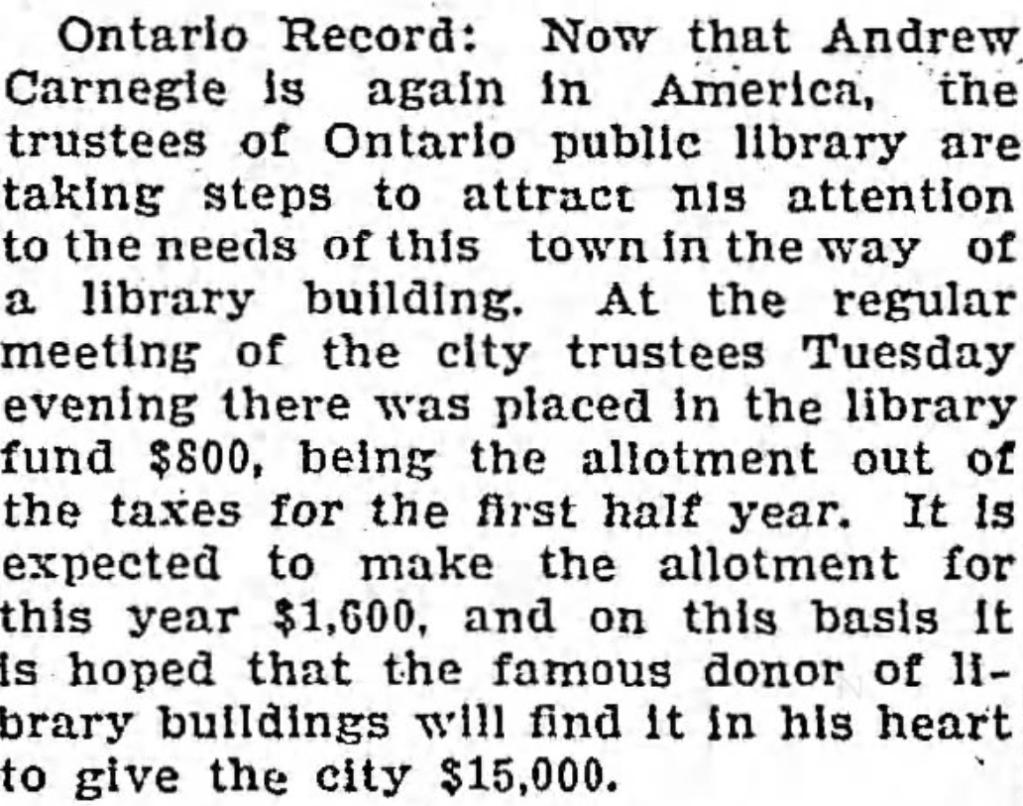

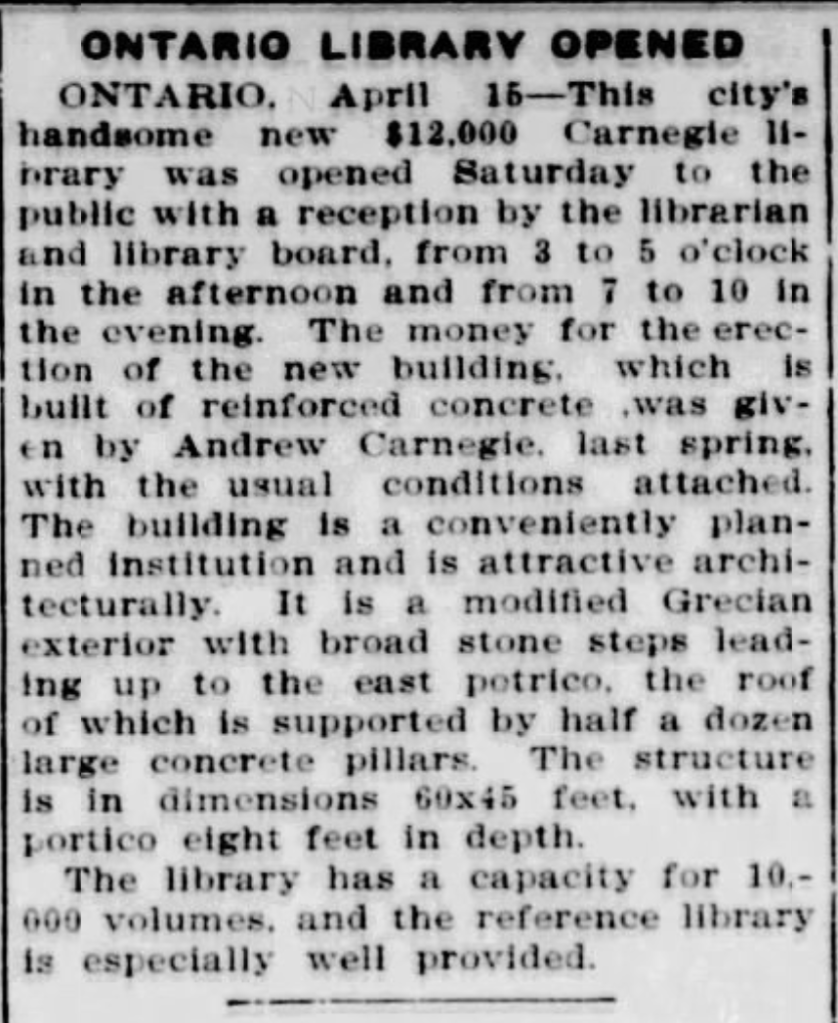

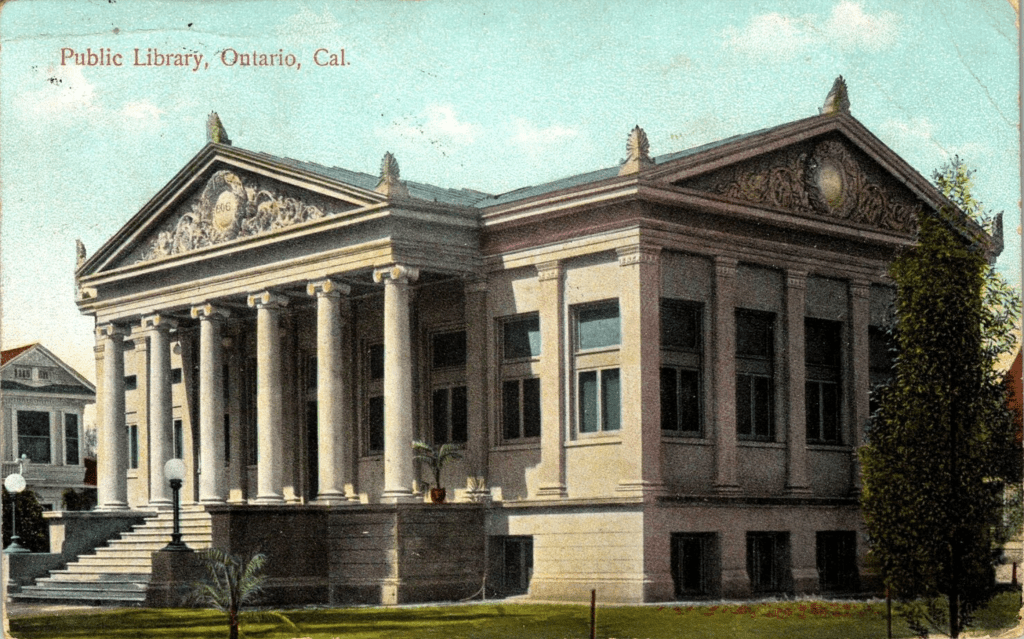

In 1903, the “Ontario Public Library” requested assistance from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to secure funds for the construction of a new library building. In April 1906, after receiving a donation of $10,000 towards the project, the head librarian, Miss Kezzie A. Monroe, visited the Covina Public Library in California, which had opened in 1905. She gathered ideas from the library tour, and Architect F.P. Burnham was hired to prepare plans for the new Ontario library building. On April 13, 1907, the new library building located at D Street and Euclid Avenue opened, stocked with approximately 3,400 volumes with plenty of room for growth.

Over the next decade, the library saw steady growth in inventory and readership, and, once again, additional space was needed, as reported by the head librarian, Miss Monroe, in the 1919 annual report.

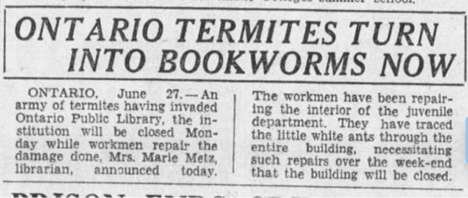

In the meantime, the Library faced trials and tribulations, such as unwanted neighbors, bees, and pests! Oh my!

As a result of vigorous action by the community to halt the conversion, Mr. Owen announced that he had “no desire to offend the people of Ontario and would place the property on the market and seek another site.”1

On July 22, 1932, the newly expanded (and insect-free!) Carnegie Library building was opened to the public. The new wing, designed by Los Angeles Architect Harry L. Pierce, nearly doubled the floor space and reading rooms.

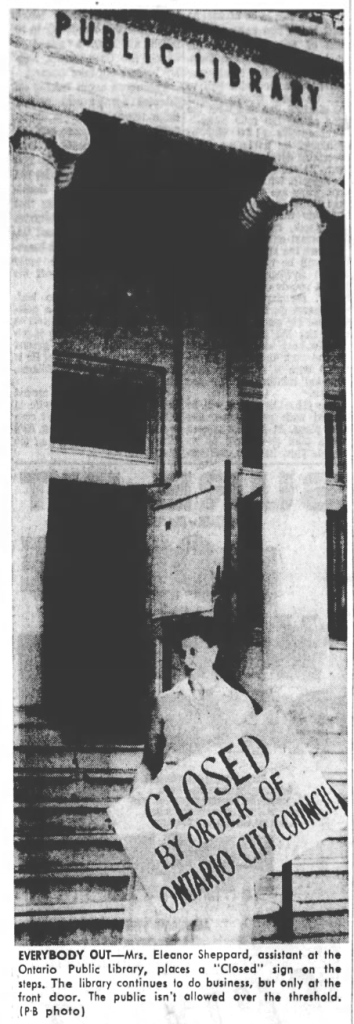

By mid-1943, the Library Board again proposed constructing a new library building. However, the selection of a new site would prove daunting. In April 1948, the Board purchased an additional lot adjoining the library property at D Street and Euclid Avenue, but an ongoing disagreement regarding the new library’s location lingered. In October 1953, the City Planning Commission approved a site at G Street and Euclid Avenue. However, having never officially reached an agreement for a new location, the library eventually fell into disrepair, and in July 1959, the library building was closed to the public, forcing the librarian to process loans and returns at the front door.

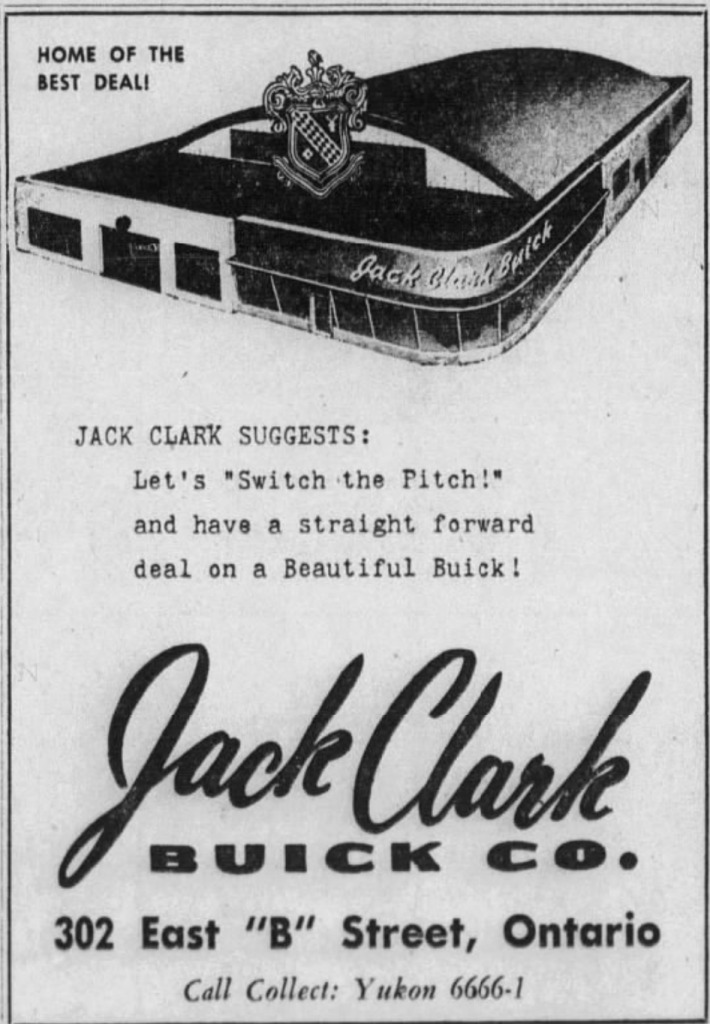

By August, the former Jack Clark Buick Co. building at 302 E. B Street was leased for use as a temporary library location. The building included a showroom, garage, and a much-needed parking lot. The temporary quarters opened on September 15 after the building’s interior was revamped for use as a library by the installation of new library shelving and 700 ft. of new fluorescent lighting. The former showroom was converted into the main reading room, and the builk of the library’s 60,000 volumes was available in the former garage.

Plans for the construction of a permanent library building on the north side of C Street between Lemon and Plum Avenues were put into motion almost immediately. By February 1960, a construction contract had been awarded to the Campbell Construction Co. of Ontario. The new library was opened to the public in mid-December 1960 and formally dedicated on January 16, 1961.

Library expansion was back in the news by April 1968 when voters overwhelmingly approved a $370,000 bond for the project. Architects Harnish, Morgan & Causey were contracted, and the expansion project began in January 1969. As part of a multi-phase plan, the library would eventually extend to the east of Plum Street. The library was expanded from 18,500 to 42,500 sq ft and was dedicated on March 1, 1970.

In 2002, the library began another expansion project, which would add an additional 11,000 sq ft. During the construction, the library was temporarily housed at the Ontario Ranch Market at 120 E. D Street. Purchase, renovation, and relocation to the temporary location cost upwards of $3M.

In 2010, the Ontario City Council renamed the library to the Ovitt Family Community Library in honor of the Ovitt family’s years of service to the city of Ontario. The Ovitt Library continues to operate at 215 E. C Street in Ontario.